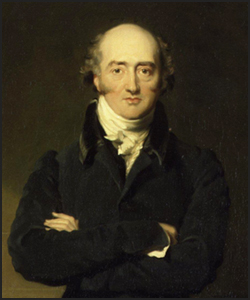

251 years ago William Wilberforce was born in a red brick house in Kingston-upon-Hull. The third child of a second son, he was a frail boy with poor eyesight but the only male heir of the Wilberforce line. The successful family business of trading wood, iron, and cloth meant that after the deaths of his father, uncle, and grandfather during his youth, William inherited enough money to live comfortably as a gentleman for the rest of his life. Instead he turned to politics and used his familial connections to the community and his fortune to get elected as a Member of Parliament for Hull at the age of 21.

At 26 he experienced his “great change” and converted to Christian evangelism. Searching for a common ground between politics and his religious beliefs, William met with a group of committed abolitionists who believed that he was the ideal man to lead their campaign in Parliament. Wilberforce’s status as an MP independent of party ties, his eloquence, and his friendship with Prime Minister Pitt made him uniquely suited for the job, but Wilberforce initially hesitated because he didn’t think that he was equal to the task. He slowly came around to the idea and later wrote: “God, Almighty has sent before me two great objects, the suppression of the slave trade and the reformation of manners”.

Wilberforce gave his first speech on abolition in 1789 and continued to present his bill in the House of Commons, facing defeat each time. In 1807 the bill abolishing the slave trade in Britain was passed and Wilberforce received a round of applause from his fellow MPs. The abolition of slavery itself in Britain occurred on July 26th, 1833, just three days before Wilberforce’s death.

Wilberforce House, where William lived until he was elected to Parliament, was sold in order to pay off debts incurred by his sons, but Hull Corporation bought the building in 1903 and turned it into a museum. It opened in 1906, making it the oldest anti-slavery museum in the world! The museum was renovated and re-opened in 2007 to coincide with the 200th anniversary of abolition. The Historical Tourist has a particular interest in Wilberforce and abolition, so visiting the museum, in the spring of 2009, was a thrill. Wilberforce House contains exhibits on slavery and the trade, the abolition campaign, the aftermath, and on modern day slavery.

Anyone who read my article on George Brown House,will not be surprised to learn that my favourite part of Wilberforce House was the library. Belonging to William and his sons, the collection was broken up in the twentieth century but visitors can view the remainder of the collection and examine Wilberforce’s books, journals, and letters through an electronic kiosk. The library is also home to a wax figure of Wilberforce created in 1933 by Madame Tussad’s for the centenary of his death. It’s a nice touch, but the Historical Tourist admits that she found the wax Wilberforce more eerie than interesting.

Other exhibits on Wilberforce present a balanced view of the man, celebrating his great successes but also mentioning the criticism he faced for supporting restrictive measures against trade unions, among other things. I enjoyed the exhibits, but did leave a little disappointed that there wasn’t more about his life and personality. Instead Wilberforce House is devoted entirely to the slave trade and the abolition campaign, showing the kidnap of Africans, the ‘Middle Passage’ across the Atlantic, and the punishing life of a plantation slave.

Draped from the ceiling, one orange flag with bold text presents visitors with a horrifying statistic:“12 Million African people were forcibly transported across the Atlantic and sold into slavery.”

I was most interested in the abolition campaign. One display case contained the famous image of Josiah Wedgewood’s chained African pleading, “Am I not a man and brother”. Wedgewood cameos were made by the pottery company using an image modeled in relief by William Hackwood. Many cameos were sold while others were given to those who supported the cause, including President of the Pennsylvanian Society for the Abolition of Slavery in America, Ben Franklin! The pieces became such a huge hit that they were worn decoratively, prompting abolitionist Thomas Clarkson to comment: “fashion, which usually confines itself to worthless things was seen for once in the honourable office of promoting the course of justice, humanity, and freedom.”

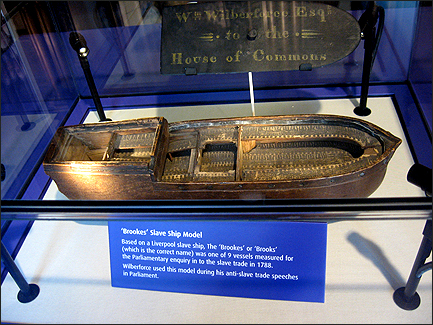

Wilberforce House also displays the Brooks slave ship model that was used by William during his speeches to Parliament to demonstrate the conditions experienced by slaves during the middle passage. Fellow abolitionist Clarkson argued that Britain should trade goods for profit with Africa instead of people. When he spoke in public meetings across the country he brought a chest filled with natural and manmade African goods along as a visual aid. Clarkson’s chest is now on display in the museum.

Sadly the abolition of slavery in the British Empire, in 1833, did not immediately result in improved conditions for slaves because slavery was replaced with a binding system of apprenticeship. Children under the age of six were freed instantly, but other ex-slaves were forced to serve an apprenticeship that was intended to prepare them for their freedom. Instead it permitted masters to continue taking advantage of their workers.

Wilberforce House’s final rooms include a look at Hull’s human rights record, as the first council to sign up for Amnesty International and as the home of the ‘Wilberforce Institute for the study of slavery and emancipation’, which opened in 2006. More sobering, are exhibits on modern day slavery. A 2005 estimate from the International Labour Organization puts the estimated number of people enslaved today at 12.3 million, a figure that includes child labour, bonded labour, and human trafficking.

For more information on modern day slavery visit Antislavery.org. To learn more about the slave trade in the eighteenth century and the abolition campaign, browse the digitized library of related documents, including essays by Wilberforce and Clarkson, here.