After taking a hiatus to concentrate on coursework, I’m returning to Truth in Fiction with a Christmas edition of Mailbox Monday. I don’t usually receive enough books to participate in the weekly meme, which encourages readers to share the new books they’ve acquired each week, but during family get-togethers after Christmas I was well-supplied with enough fiction and non-fiction to ward off the boredom of a long Canadian winter.

Mailbox Monday began at The Printed Page but is now being hosted on a monthly basis as the ‘Mailbox Monday Blog Tour’. For the month of January it can be found at Rose City Reader.

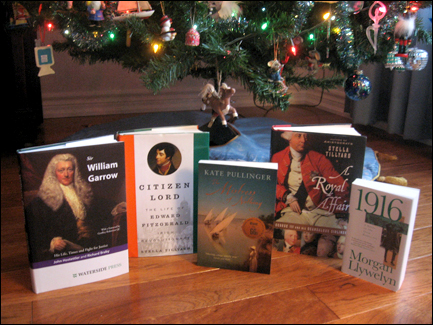

Sir William Garrow: His Life, Times and Fight for Justice has been on my wish list for awhile so I was thrilled to find it under the tree! Written by legal historian John Hostettler and Richard Braby, a descendant of Garrow’s, it details the life of Sir William Garrow, an eighteenth century lawyer who changed the English criminal trial. Garrow spent the first ten years of his career as a defender at The Old Bailey and became known for his aggressive cross-examination, but later in life he changed sides and conducted prosecutions against political radicals while his colleague, Lord Erskine, defended them and became the more celebrated lawyer. Garrow’s early career has been dramatized in the wonderful British drama Garrow’s Law, which concluded its successful second season in December.

For my birthday several months ago my Aunt gave me Aristocrats, Stella Tillyard’s biography of the Lennox Sisters who became influential in Georgian England, so it was only fitting that I received Tillyard’s other titles, A Royal Affair and Citizen Lord: The Life of Edward Fitzgerald, Irish Revolutionary from her for Christmas.

A Royal Affair is concerned with King George III of England and his siblings, primarily his sister Caroline Mathilde whose affair with a court doctor ended in tragedy. Also featuring the king’s brothers, who delighted the gossip-hungry press by partying and carrying on disastrous relationships, Tillyard’s biography suggests that George III’s refusal to give up America can be attributed to his desire to control the colonists in the same way that he tried to rule his siblings.

Her other title, Citizen Lord, chronicles the life of Lord Edward Fitzgerald, a Dubliner who fought with the British in the American War of Independence, visited revolutionary France, and took part in the 1798 Irish rebellion. A blurb on the back of the work writes that Lord Edward “grew up as vigorous as Garibaldi and passionate as Byron”. That description alone is enough to pique my interest!

Continuing with the Irish theme, I received Morgan Llywelyn’s 1916: A Novel of the Irish Rebellion. I first borrowed this fictionalized account of the Easter Rising from the library last March as part of the Ireland Reading Challenge, and am thrilled to have my own copy of this fantastic novel to re-read and keep. You can find my review of it here!

My final historical addition is Kate Pullinger’s Mistress of Nothing. The novel, which won the 2009 Governor General’s Literary Award recognizing excellence in Canadian literature, is loosely based on the writings of Lady Lucie Duff-Gordon. Lady Duff-Gordon moved to Egypt in order to help manage her tuberculosis and published Letters from Egypt in 1865. Pullinger’s novel places Sally, the lady’s maid accompanying her, as the narrator who eventually must learn that despite the new freedoms life in Egypt has granted her, she is ultimately mistress of nothing.

I was also fortunate enough to receive a pair of fantasy novels to read when I’d rather escape to another world than the past. I’ve been meaning to read Good Omens by Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman for awhile and asked for the novel this Christmas in the hopes of finally sitting down to read it. This collaboration by two of the biggest names in fantasy was nominated for the World Fantasy Award in 1990 and concerns the efforts of the angel Aziraphale and the demon Crowley to postpone the end of the world after the apocalypse is announced.

Lev Grossman’s The Magicians tells the story of a teenager, Quentin Coldwater, disappointed in real life and secretly fascinated by a series of fantasy novels set in a magical land of Fillory. Life becomes much more interesting when he’s admitted to a college of magic in New York and discovers that Fillory is real, but he soon realizes that the reality is darker than his childhood fantasy and more dangerous.