Standard dueling procedure was to send a friend with a note asking for satisfaction shortly after an insult occurred. In 1798, Prime Minister William Pitt had accused opposition Member of Parliament George Tierney of harboring a desire to ‘obstruct the defense of the country’ and was challenged the next day, yet Lord Castlereagh waited a full nine days before demanding satisfaction from George Canning.

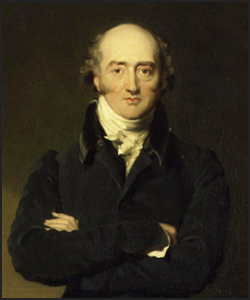

In those nine days Castlereagh learned nothing new, but his resentment grew after he was shown the months worth of correspondence that took place behind his back. Letters revealed that all of his colleagues had agreed that he should be removed from office as Secretary of State for War and the Colonies and, in a more damaging blow to his pride, that they had thought him incapable but continued to act as though he had their full confidence while making important decisions regarding the war with France. Although Canning was not the only man involved in the deception, and not the most deserving of blame, the Duke of Portland was elderly and had suffered a stroke in August, and Castlereagh’s uncle Lord Camden’s selective retelling of events had made Canning the target of his wounded pride.

As he had guessed back in July, Canning took the blame, which came in the form of an unusually worded challenge. Challenges were usually notes that asked for an explanation of the perceived insult and demanded satisfaction, but Castlereagh’s long note reads more like a compilation of grievances. “You continued to sit in the same cabinet with me,” he writes, “and to leave me, not only in the persuasion that I possessed your Confidence and Support as a Colleague, but… to originate and proceed in the Execution of a new Enterprize [referring to the failed Walcheren Expedition] of the most arduous and important nature with your apparent concurrence and ostensible approbation.”

Although the challenge addressed the dishonourable conduct in detail, what it didn’t do was give Canning a chance to respond to the allegations levelled against him. In fact, fellow Member of Parliament William Wilberforce later called it ‘a cold-blooded measure of deliberate revenge’, although he strongly disapproved of dueling in general. Canning sent his reply to the challenge the next day:

My Lord, The Tone and the Purport of your Lordship’s letter (which I have this moment recieved) of course preclude any other answer, on my part, to the Misapprehensions and misrepresentations with which it abounds, than that I will cheerfully give to your Lordship, the Satisfaction which you desire.

The duel was set for the morning of September 21st, 1809 at Putney Heath.

Although duels were slowly becoming less murderous, there were still fatalities and participants used the night before the duel to put their affairs in order. Canning wrote a letter to his wife Joan that reads as a farewell… and for good reason. Lord Castlereagh was known as a good shot while Canning had never fired a pistol in his life. Reflecting on the events leading up to the challenge, he wrote that,

“The poor old Duke’s procrastination and Lord Camden’s malice or mismanagement have led [to these] circumstances. If anything happens to me, dearest love, be comforted with the assurance that I could not do otherwise than I have done… I hope that I have made you happy; and if I leave you a happy mother and a proud widow, I am content. Adieu, Adieu.”

The next morning Canning and Castlereagh’s seconds, whose job was to ensure fairplay and attempt to defuse the situation, decided on a distance of twelve paces (one of the longer distances between participants) and that both would shoot at the same moment. Both statesmen missed their first shot and Castlereagh’s second Yarmouth commented that it was a pity Canning hadn’t fired into the air because his friend would be unable to demand a second shot honourably under those circumstances. Instead, the seconds agreed that a second shot would be the last regardless of the result. Canning’s second shot also missed, but Castlereagh’s hit his opponent in the thigh. Agreeing that honour had been satisfied, Canning was helped off the field.

Undoubtedly the wound put him out of commission while he recovered, but Canning had been fortunate that the bullet missed all major arteries, only passing through ‘the fleshy part of the thigh’. He wrote a reassuring letter to his aunts later that day:

Pray, young women, had either of you ever a Ball pass through the fleshy part of your thigh? If not you can hardly conceive of how slight a matter it is…if you have a mind to try the experiment, I would recommend Lord Castlereagh as the operator. For here I am just as well as if I had not undergone the operation two hours ago – without pain, without fever, and with only two little holes which I daresay you could see through… upon my word of honour there is not the slightest danger, pain, or inconvenience in my wound.

Although both statesmen had survived the duel, they were now faced with navigating the murky waters of public opinion…