By now most will have heard of The King’s Speech, the critically acclaimed film that tells the story of The Duke of York (later King George VI)’s struggle to overcome his stammer. Although Bertie, as he was known to his family, had previously tried a number of treatment options, it is Australian speech therapist Lionel Logue’s unorthodox combination of breathing exercises, tongue twisters, and talk therapy that finally proves effective. When the King dies, older brother David ascends the throne as King Edward VIII, but his infatuation with Wallis Simpson, a twice divorced American woman, threatens to bring down the government. With World War II just around the corner and Bertie first in the line of succession, Bertie’s ability to speak is more important than ever.

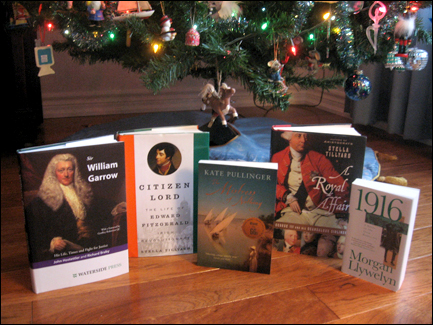

The King’s Speech was one of my favourite films of 2010 and I left the theatre wanting to know what had really happened. My research began with a copy of Mark Logue and Peter Conradi’s book The King’s Speech: How one man saved the British Monarchy. Based on the diaries kept by Lionel Logue, and on his correspondence with George VI, the book was written after filming began, meaning it isn’t the source material behind the Academy Award winning film. While the movie dramatizes George VI’s struggle, the book was written by Mark Logue, Lionel’s grandson, to “tell the story of my grandfather’s life from his childhood in Adelaide, South Australia, in the 1880s right the way through to his death”.

Conradi and Logue’s book is a great source and complements the movie nicely, but the critical and popular success of the film has ensured that it receives more press than most period dramas and, as a result, that there is more written about its historical accuracy.

In order to examine them all, it is prudent to divide criticisms into two categories; the accuracy of the central relationship between Logue and Bertie depicted in their treatment sessions, and the historical events that serve as the background for their relationship, including the abdication and the rise of Hitler.

Most articles criticize The King’s Speech for its treatment of relevant events but pay little attention to the central relationship of Bertie and Lionel. The main change here is a tightening of chronology. The film begins their sessions in 1934, but Bertie actually began visiting Logue in 1926. By the early thirties his speech had improved so dramatically that he rarely visited Logue’s Harley Street premises, but when the abdication crisis resulted in his ascension to the throne, George VI again turned to Logue for help.

Lionel Logue (Geoffrey Rush) and Bertie (Colin Firth) have a session.

Logue’s diaries did not record his sessions with the King, but scriptwriter David Seidler drew from his own experiences as a stutterer to decide on both the treatments Bertie would have tried, and on the methods Logue used with his patients. Seidler’s theories were confirmed when he learned that his uncle was a former patient of Logue’s and that the talk therapy depicted in the film was one of the methods the speech therapist had used.

Although it makes for a humourous scene in the film, Lionel’s wife Myrtle did, in fact, know about her husband’s most famous patient. She was even “presented” at court to Bertie’s parents in a show of gratitude for Lionel’s work and wrote an article for an Australian newspaper about the experience!

Another humourous moment is more accurate. At the film’s climax Bertie broadcasts a speech immediately after Britain’s Declaration of War against Germany but Lionel remarks that he made one mistake. While the exchange that follows did take place, it actually occurred after another speech given by the King in December 1944 to mark the disbanding of the Home Guard. The only mistake was a stumble over the ‘w’ in weapons.

“Afterwards Logue shook hands with the King and, after congratulating him, asked why that particular letter had proved such a problem.

‘I did it on purpose,’ the King replied with a grin.

‘On purpose?’ asked Logue, incredulous.

‘Yes. If I don’t make a mistake people might not know it was me.’” (p 200 *)

While the timeline has been compressed and the lack of formality in Bertie and Lionel’s friendship is likely exaggerated, they did remain friends until the end of their lives and the film is essentially accurate in this portrayal. However, press have focused on the historical events that provide the background for the film, and here The King’s Speech takes more liberties.

Elizabeth (Helena Bonham Carter) supports her husband.

The biggest change is that Winston Churchill actually supported Edward VIII (later given the title the Duke of Windsor) during the abdication crisis. This was more dangerous than the film makes out because Bertie’s brother was not just spoiled and naive; he was also suspected of being a Nazi sympathiser. Even after his abdication and forced exile the British Government thought that the Duke of Windsor’s willingness to enter an alliance posed a threat and he was sent to govern the Bahamas. In his draft of a telegram informing the Prime Ministers of the Dominions that the Duke had been appointed Governor of the Bahamas, Churchill wrote “The activities of the Duke of Windsor on the Continent in recent months have been causing His Majesty and myself grave uneasiness, as his inclinations are well-known to be pro-Nazi and he may become a centre of intrigue.” The sentence was omitted from the final version.

As shown in The King’s Speech, Edward VIII’s father even doubted his eldest son’s ability to rule. Before his death, George V, said about his younger son Bertie and granddaughter Elizabeth, “I pray to God that my eldest son [Edward] will never marry and have children, and that nothing will come between Bertie and Lilibet and the throne”. He also made a prediction about Edward, confiding to Prime Minister Baldwin that “After I am dead, the boy will ruin himself in 12 months.”

Churchill’s support of Edward VIII during the abdication crisis meant that George VI was, in turn, not a great supporter of Churchill. The Royal Family were in favour of a policy of appeasement, and after Chamberlain signed the Munich Agreement he was invited to appear on the Palace balcony with George VI and his wife in a show of support. This endorsement of foreign policy by the Royal Family has been called “the most unconstitutional act by a British sovereign in the present century” by historian John Grigg.

Although the film undoubtedly takes liberties with historical facts, It remains a moving film with wonderful dialogue, a great cast, and a musical score that should be celebrated. It is important to acknowledge, discuss, and understand the inaccuracies present in The King’s Speech, but these deviations from historical fact don’t take away from the central story of Logue and George VI’s friendship and the King’s success in overcoming his crippling stammer.

Verdict: Its Oscar success was well-deserved. This is a film that everyone should see and the book is a wonderful complement for those interested in learning more.

The King’s Speech is released on DVD & Blu-Ray today.

The King’s Speech: How one man saved the British Monarchy by Conradi and Logue is available now.

* Peter Conradi and Mark Logue. The King’s Speech. Toronto: Penguin Canada, 2010.